R. Joseph Ben Abraham Gikatilla

A Medieval Sephardi Kabbalist

By Marvin J. Heller1

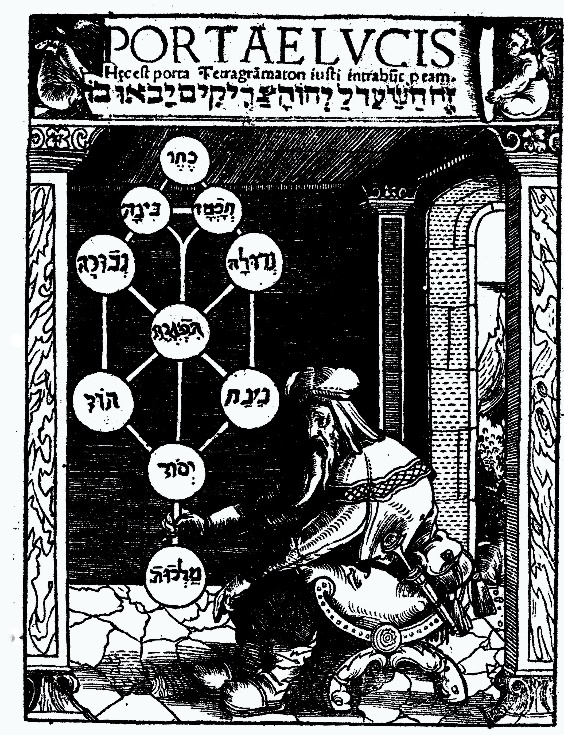

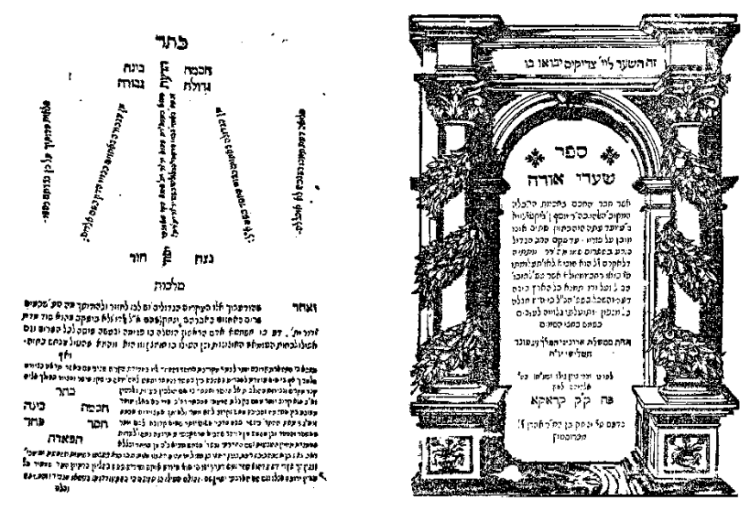

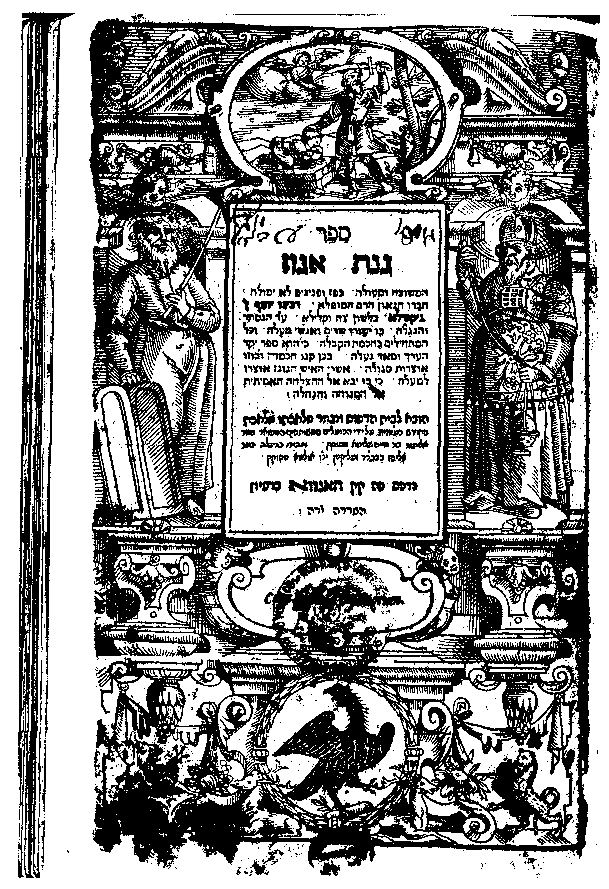

1516, Portae lucis (Sha’arei Orah)

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Among the highly regarded and leading medieval kabbalists is R. Joseph ben Abraham Gikatilla (Chiquitilla) (1248–c. 1325). Important and influential, Gikatilla was the author of several works, all republished, some frequently. Nevertheless, he is, as with many other early important and distinguished rabbinic individuals of account, not well-recalled today by most members of the community he so influenced.

This article is, not to be too repetitive, one of several recalling sages, prominent, preeminent, and highly regarded in their time, but not well-recalled today outside of rabbinic and academic circles.2 R. Joseph ben Abraham Gikatilla, unfortunately, falls into that circle, not being remembered despite his importance and his contribution to Jewish kabbalistic literature.

Born in Medinaceli, Castile, Gikatilla for many years was a resident of Segovia. Interested at an early age in philosophy, Gikatilla reportedly had considerable knowledge of secular sciences, and was familiar with the works of Ibn Gabirol, Ibn Ezra, Maimonides, and others. He wrote a commentary on Maimonides’ Moreh Nevukhim (Venice, 1574), in She’ilot le-Hakham of Saul ha-Kohen. However, he subsequently became opposed to the study of pure philosophy.3

Gikatilla was a disciple and the foremost student of the noted kabbalist, R. Abraham ben Samuel Abulafia (1240-c. 1291). Moses Idel notes that Abulafia praises Gikatilla as “his most successful pupil.” Abulafia, born in Saragossa, in Aragon, is among the earliest and foremost kabbalists. Idel credits Abulafia as being the “founder of the prophetic Kabbalah.” Abulafia wrote “great manuals which are textbooks,” which are textbooks of meditation on the Sacred names and the letters of the alphabet, still copied to the present. Hersh Goldwurm writes that Abulafia authored twenty-six books plus twenty-two more containing descriptions of his vision. Despite this, the Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book attributes one book only, and that in one edition, to Abulafia, Sheva Nativot ha-Torah (Leipzig, 1854).4

Abulafia was a wanderer, leaving for Eretz Israel when twenty. In 1280, he travelled to Rome for the purpose of converting Pope Nicholas III to Judaism. The Pope, according to Goldwurm was vacationing in Suriano at the time, heard of Abulafia’s plans and ordered that the fanatical Jew be burned upon his arrival. Despite a stake having been erected for that purpose, Abulafia continued on his way. Arriving there, he learned that the Pope had died of a stroke the previous night. Abulafia returned to Rome where he was imprisoned for four weeks, but was then released, and continued on to Sicily.5

Initially greatly influenced by Abulafia’s ecstatic, prophetic system of kabbalism, Gikatilla soon displayed a greater affinity for philosophy. Idel credits Gikatilla with having made an original attempt to provide a detailed yet lucid and systematic exposition of kabbalism.”6 Gikatilla expounded and, in his early writings, publicized the teaching of his mentor, Abulafia. Intellectually, Gikatilla, although initially much influenced by Abulafia’s “prophetic Kabbalah,” later became an adherent of theosophic (philosophic-mystical) Kabbalah. A person of great piety and credited with miraculous deeds, Gikatilla, was known as ba’al ha-nissim (master of miracles).7

Gikatilla’s influence was widespread. Apart from his kabbalistic impact, he is also noted in halakhic works, most notably by R. Joseph Caro (1488–1575) in his Beit Yosef and Maggid Mesharim, where his maggid (heavenly mentor) refers positively to Gikatilla, and in a responsum concerning the blessing for the new moon.8 Another kabbalist with whom Gikatilla was associated and was close to is R. Moses de León (Moshe ben Shem Tov, c. 1240 – 1305), each influencing the others work.9

Yeshayahu Vinograd, in the Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book, records five published titles by Gikatilla. The following descriptions of those titles are in the chronological order of their initial printing. We begin with Sha’arei Orah, a kabbalistic work on the Sefirot, Gikatilla’s most important and most reprinted work, written prior to 1293. It is a fundamental work of Kabbalah. R. Isaac Luria (ha-Ari ha-Kadosh, Arizal, 1534-72) describes Sha’arei Orah as, “the key to mystical studies.”10 Sha’arei Orah, intended as an introduction to the wisdom of the Kabbalah, defines, explains, and analyzes the ten Sefirot, and kabbalistic symbolism and their relation to Scriptural symbols. In doing so, Sha'arei Orah relies heavily on the Zohar, although Gikatilla also often departs, quite originally, from that work.11

1516, Portae lucis (Sha’arei Orah)

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

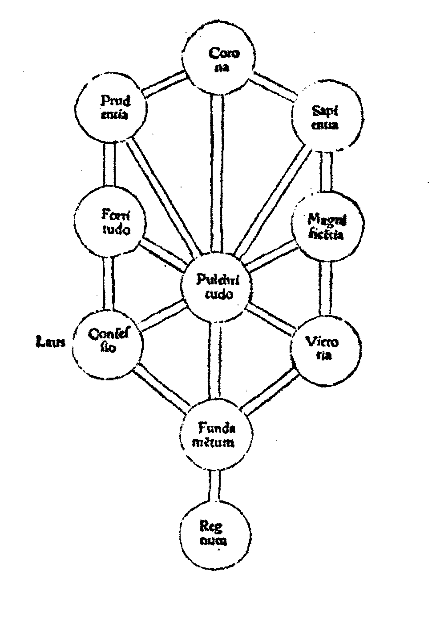

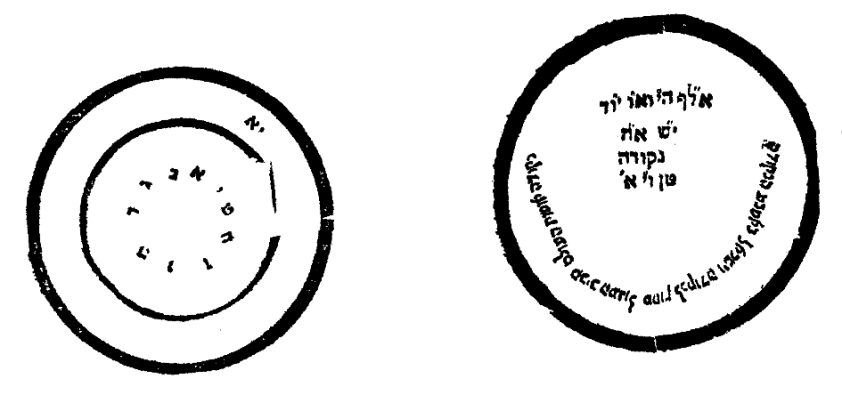

The first printing of Sha’arei Orah (Portae lucis) was a Latin edition with the descriptive subtitle H[a]ec est porta tetragram[m]aton iusti intrabu[n]t p[er] eam. 'This is the gate of the Tetragrammaton for the righteous to enter through it', that is, the Tetragrammaton, the four letter Divine name. Portae lucis was printed in Augsburg in 1516 at the press of Johann Miller, active in Augsburg from 1514 – 1520, in quarto format (40: 110 pp.). The translation of Sha’arei Orah to Latin was by Paulus Ricius (Paulus Israelita, 1480-1541), an apostate, but also an important Christian kabbalist. The title-page woodcut (above) is by Hans Burgkmair, the Elder (1473–1531), a German painter and woodcut printmaker. The title page has the first printed woodcut image of the Sefirot, a much reproduced woodcut of the Sefirot. A second illustration of the Sefirot (left) accompanies the text. The first printed image of the Sefirot did not appear in a Hebrew book until seventy-six years later when printed in Cracow in 1592 in an edition of Pardes Rimmonim.12

A prolific writer, this is Ricius’s best known work. As ordered by Emperor Maximilian, he also translated, several tractates of Mishnayot, the earliest known renderings in Latin of the Mishnah. Paulus’s son, Jerome Riccio (Hieronymus Ricius), sent a copy of Portae lucis to Johannes Reuchlin (1455-1522), the famous German Hebraist; an architect of the Christian Kabbalah and a defender of the Talmud and Jewish scholarship against the attacks of the apostate Johannes Pfefferkorn and other “obscurantists.” Reuchlin’s works were influenced by Ricius’ Portae lucis.13

The publication of Portae lucis by Christian Hebraists was not a unique phenomenon, but rather reflects the interests of contemporary Christians in Jewish mysticism. According to John Edwards, some Christian students were fascinated by an older Jewish mystical tradition, “Cabbala,” which helped them to improve their understanding of God and “to approach Him more nearly, and to help bring the world into greater accrdance with His will.” As a result, according to David B. Ruderman, Christian printers “were actually the first to publish kabbalistic books in the sixteenth century.” He notes that, in contrast the reactions of contemporary Jews were mixed to what for them was an esoteric law.14

1561, Sha’arei Orah. The first two Hebrew editions of Sha’arei Orah were both printed in 1561 in Mantua and Riva de Trento. The Mantua edition was published at the press of Jacob ben Naphtali ha-Kohen of Gazzuolo. The colophon dates completion of the work to 20 Tamuz, 321 (Friday, July 14, 1561). Mantua is among the early cities of importance in Hebrew printing in the incunabular period; Abraham ben Solomon Conat, with the assistance of his wife Estillina, printed some of the earliest Hebrew books here. It is the second Hebrew printing city of importance in Italy in the sixteenth century, with close to two hundred titles to its credit. Among the Hebrew printers in Mantua in the sixteenth century is Jacob ben Naphtali ha-Kohen of Gazzuolo, who had also previously been associated with the Sabbioneta press. Among the titles he printed were, in addition to of Sha’arei Orah, several important kabbalistic titles such as, Tikkunei Zohar, Ma'arekhet ha-Elohut with the commentary Minhat Yehudah, and the Zohar.

The Tyrolese town of Riva di Trento, better known for the Trent Blood Libel of 1475 and the Councils of Trent from 1545 to 1563 which formulated the Church response to the Reformation, is the source of an unusual episode in the history of the Hebrew book. For a short time, from 1558 to 1562, it was a refuge for the Hebrew book; one in which about forty Hebrew titles were printed. Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo (1512-78), Cardinal of Trent was the patron and protector of a Hebrew press in Riva di Trento; it was also a source of revenue for him.15 Madruzzo as a scholar and supporter of learning argued at the Council of Trent (1562) for leniency and moderation in condemning books.

The Jewish founders of the press are R. Joseph Ottolenghi (d. 1570), originally of Ettlingen, in Baden, Germany, reflected in its Italianized form in his name, rosh yeshivah at Cremona. Under his tutelage, Talmudic studies had continued in Cremona after that work had been banned and burned elsewhere. R. Jacob Marcaria, a physician and a dayyan on the bet din presided over by Ottolenghi, was recruited by Madruzzo help finance and play a role in the press. The press was located in the house of Antonio Broën.

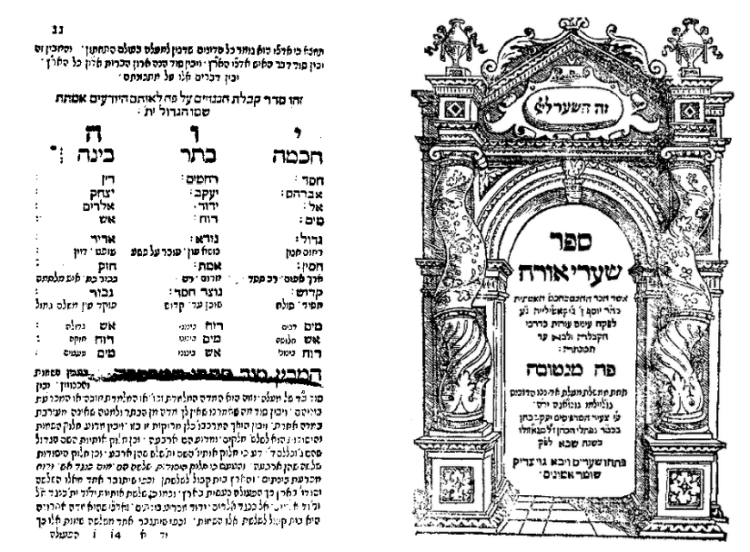

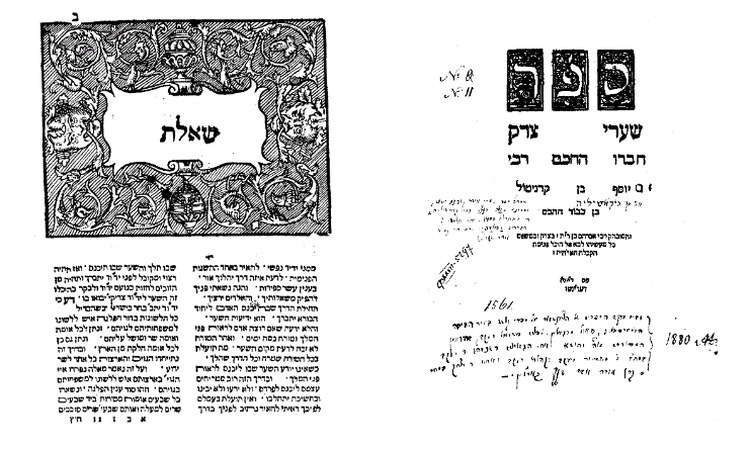

1561, Sha’arei Orah, Mantua

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The Mantua edition of Sha’arei Orah, published in quarto format (40: 92 ff.), has the architectural pillars typical of Mantua imprints from this period. The text, with rare exceptions, is set in rabbinic letters in one column. In contrast, the Riva di Trento edition, also published in quarto format (40: 84 ff.) is set in two columns in square letters. Neither edition has the Sefirot diagram. Other parts of the text of both editions have small sections that emphasize textual entries.

The Riva di Trento edition (40, 84 f.) of Sha'arei Orah is set in square letters in two columns; it is not dated.Apart from the fact that the Riva press was short lived, its publication date is determined from the colophon, the printer requesting the merit to complete Sha’arei Orah as they have just finished Sha’arei Zedek (1561).

1561, Sha’arei Orah

Mantua ed. on the left - Riva de Trento

ed. on the right

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

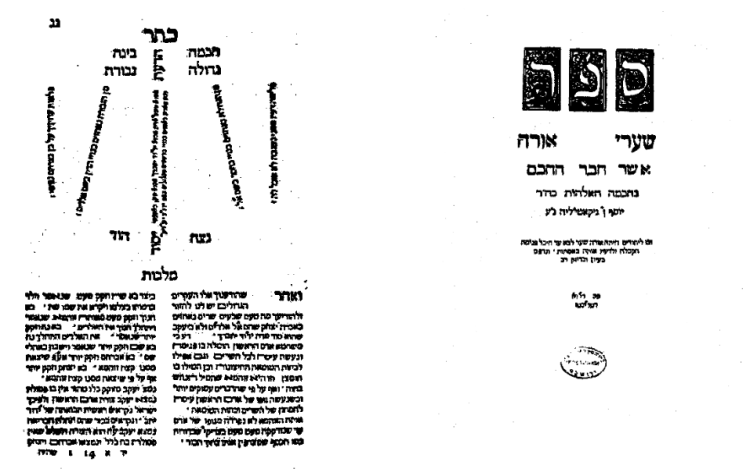

1600, Sha’arei Orah. The next edition of Sha’arei Orah was published in Cracow in 1600 at the press of Isaac ben Aaron Prostitz. It, too, is in quarto format (40: 116 ff.). The Prostitz press, founded in 1569 by Isaac ben Aaron of Prostitz, continued to print books well into the seventeenth century. Isaac Prostitz, advanced in years, left the press in about 1600, to return to his birthplace, Prossnitz (Prostejov) in Moravia.

This edition is significant as it is accompanied by a commentary by R. Mattathias ben Solomon Delacrut (16th century). Delacrut, both a kabbalist and astronomer, translated several Latin texts on the latter subject into Hebrew. Among his students in Kabbalah was R. Mordecai Jaffe (c. 1535-1612), author of the Levush. Delacrut’s commentary on Sha’arei Orah was brought to press by R. Abraham ben Eliezer Didelson of Posen from a manuscript belonging to Delacrut’s son R. Joseph Delacrut, author of Hiddushei Halakhot on Tractate Eruvin (Lublin, [1605]).

1600, Sha’arei Orah, Cracow

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

The title page, with a frame identical to that employed by the Di Gara press in Venice, states that Sha’arei Orah was,

until now as a sealed vision, not truly understood, until the great rav, “known in the gates” (Proverbs 31:23), arose. He is R. Mattathias Delacrut, who brought to light that which was concealed with a comprehensive commentary. By his so doing the world is filled with knowledge, insight, and intelligence through the above work, for he [Delacrut] revealed all that was concealed, and its value is apparent to the eyes as the sun at midday. . . .

The title page is dated “Be glad then, you children of Zion, and rejoice (360 = 1600) ושמחו in the Lord your God” (Joel 2:23). Delacrut’s introduction follows and includes a small line chart of the Sefirot, similar to that of the Mantua edition. The text, in a single column, is in rabbinic letters in two sizes, for the text and commentary. At the end of the volume is an epilogue from Didelson, who expresses his prayer that he might also print Delacrut’s commentary on a work still in manuscript. Below it is a representation of a sheep, representative of Akedat Yitzhak (Genesis 22:1-19) and alluding to the printer, Isaac (Yitzhak) Prostitz. About it is a piyyut from the Yom Kippur liturgy by Rabbenu Gershom. It is the only reported usage of this pressmark.16 Sha’arei Orah was reprinted four times in the following century, all with Delacrut’s commentary, and has been reprinted several times since.17

1600, Sha’arei Orah, Cracow

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

Sha’arei Orah’s influence is evidenced by the significant personages who quote or reference it. Among them are R. Moshe Cordevero, R. Joseph Caro, as noted above, R. Chaim Vital, R. Isaac ha-Levi Horowitz (Shelah ha-Kadosh), R. Judah Aryeh Leib Alter (Sefat Emet), R. Shem Tov ibn Shem Tov, R. Moses al-Ashkar, and R. Judah Hayyat, as well as lengthy extracts from it inserted by R. Reuben ben Hoshke in the Yalḳuṭ Reubeni. 18

1561, Sha’arei Zedek. Another work on the Sefirot by Gikatilla is Sha’arei Zedek, also published in Riva di Trento by the Marcaria press. It, too, is in quarto format (40: 52 ff.). It has a spare title-page, comparable to that of Sha’arei Orah, but here states that it is “‘with righteousness and justice’ (Hosea 2:21) with all his deeds in order to come to the inner Temple of Divine reception.” Sha’arei Zedek was printed prior to Sha’arei Orah but is listed here after that work due to the first printing of the former title in Latin. Several passages in Sha’arei Zedek were reprinted unchanged in Sha’arei Orah, others reworked and expanded.19

The subject addressed in Sha’arei Zedek is the Shekinah, the divine presence. Among the concepts expressed in Sha’arei Zedek, as described by Gershom Scholem, is,

the premise that one and the same Torah could be revealed in a different form in each shemittah . . . and was even extended by some who maintained that the Torah was read differently in each of the millions of worlds involved in the creation - a view first expressed in Gikatilla’s Sha’arei Zedek.20

In Sha’arei Zedek, Gikatilla provides another explanation of the theory of the Sefirot, reversing their normal succession.

1561, Sha’arei Zedek

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

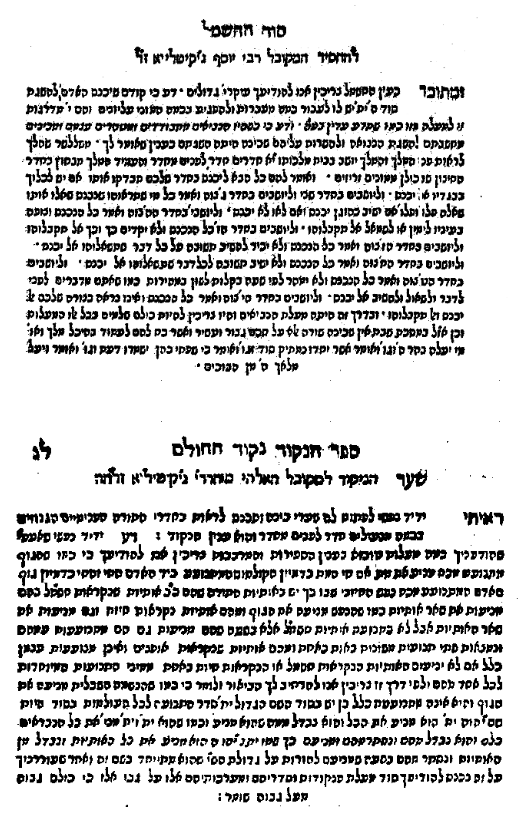

1601, Sefer ha-Nikud; Sod ha-Hashmal. In 1601, two of Gikatilla’s works, Sefer ha-Nikud and Sod ha-Hashmal, were published. Both were included in Arzei Levanon, Lands of Lebanon (Isaiah 14:8, Psalms 104:16), a compendium of seven small independent works, “sweeter also than honey and the honeycomb” (Psalms 19:11).21 Arzei Levanon was published in Venice at the press of Giovanni di Gara in quarto format (40: 50 ff.). Sefer ha-Nikud, comprising folios 33a-40a, is a mystical explanation of the vocalization and deeper meaning of the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet; Sod ha-Hashmal (40b-42a) is on the vision of Ezekiel.

1561, Sod ha-Hashmal on top

Sefer ha-Nikud on the bottom

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

The title-page of Arzei Levanon, has an architectural border with standing representations of the mythological Mars and Minerva with shields, above them vines and fruits.22 That quarto frame was employed by Francesco Minizio (Giulio) Calvo, a printer of Latin and Italian books in Rome (1521-34) and Milan (1539-45). The text informs that these works, albeit small in size, are great in value and have not been printed previously. Small print at the bottom of the page informs that the printer was assisted in bringing Arzei Levanon to press by R. Nissim Shoshan and the young Elishama, son of the elder craftsman Israel Zifroni. The text is in a single column in a small rabbinic type. Sefer ha-Nikud and Sod ha-Hashmal were reprinted together in 1648 in Cracow at the press of Menahem Nahum ben Moses Simon Meisels in octavo format (80: 13 ff.).

1600, Arzei Levanon - Sefer ha-Nikud

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

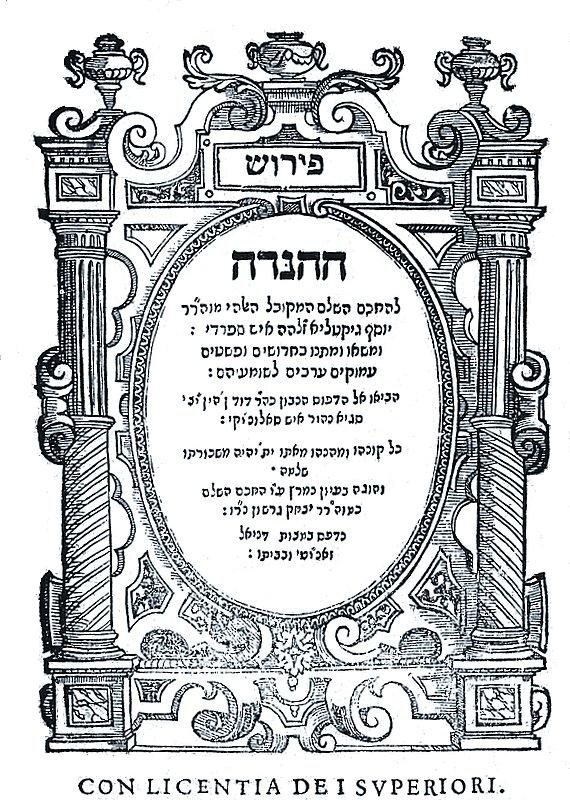

1602, Perush ha-Hagadah. Our next Gikatilla work is a Kabbalistic commentary on the Pesah Haggadah, published in Venice at the press of Daniel Zanetti in quarto format (40: [10] ff.). The Zanetti family press, established by Matteo Zanetti, was active from 1596 to 1608, publishing more than sixty titles.23 Perush ha-Hagadah was brought to press by R. David ibn Hin, sagi nahor (with excess of light, that is, blind) of Salonika. It was edited by R. Isaac Gershon.

1602, Perush ha-Hagadah, Venice

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

The title page of Perush ha-Hagadah has the Zanetti pillared frame and its text informs that the Sephardi kabbalist Gikatilla was busily engaged in (lit. carrying and giving ומשאו ומתנו) novellae and deep literal interpretations, sweet to the hearer. The title page is not dated; the publication date is known from Likkutei Shoshannim, also brought to press by ibn Hin.24

The text is in a single column in a small rabbinic type, excepting headers and initial words which are in square letters. The text is not accompanied by images. Although the designation Zafenat Pa’ne’ah (revealer of hidden things, Genesis 41:45) does not appear on the title page, that is how Gikatilla refers to this commentary in the beginning of his introduction, where he writes that in it,

he reveals those things that are concealed according to the truth of Kabbalah, for Joseph is the ruler over the recounting of the redemption from Mizraim, he is the provider משביר for all the nations of the world, the pious will rejoice in honor, he will sing on the couch of his resting place in Gan Eden. “The Lord make his face shine upon you” (Numbers 6:25) my brother and He will open your eyes with the light of His Torah and guide you with His direction in order that you might know the “signs and wonders” (Deuteronomy 6:22) of His might through which a person can enter into the loftiness of His love.

Perush ha-Hagadah was republished in R. Moses ben Shem Tov de León’s Nefesh ha-Hokhmah (Basle, 1608) and in Hemdat Yamim III (Livorno, 1764).

1615, Ginnat Egoz. This is a Kabbalistic work on the gematriot of the names of God and related subjects. Ginnat Egoz was published in Hanau in folio format (20: 75 ff.) at the press of Eliezer ben Hayyim and Elijah Zulkiman Ulma. Gikatilla wrote Ginnat Egoz when only twenty-four and reflects the influence of Abulafia, as opposed to the theosophic (philosophic-mystical) Kabbalah of which, as noted above, he later became an adherent.

The title is from “I went down into the garden of nuts (ginnat egoz) to see the fruits of the valley, and to see if the vine had blossomed, to see if the pomegranates were in bloom” (Song of Songs 6:11), alluding to the book’s contents, ginnat standing for ג gematria, נ notarikon, and ת Temurah. Egoz is that which is concealed, for “The secret things belong to the Lord our God; but those things which are revealed belong to us and to our children” (Deuteronomy 29:28). Egoz (the nut) is the emblem of mysticism.

1615, Ginnat Egoz, Hanau

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

The title-page has an elaborate frame like that used in Hanau previously by Hans Jacob Hena with the quarto Nishmat Adam (1611) but here varying from it in several details, including added decorative material at the bottom of the page. The text is primarily in black, the title and several lines in red. It states that the contents are in the manner of nistar (concealed) and niglah (revealed). The colophon dates completion of the work to Wednesday, erev Rosh HaShana טוב משיח (September 23, 1615 = 375)

Ginnat Egoz is divided into three parts, each subdivided into she’arim. The contents include sections on the Tetragrammaton, the various names of God; the second on numbers, emanating from the Tetragrammaton (37a-40a), that is, the Heikhalot, stars; Lekhet, the soul; candles of the menorah; days of the festival; seven lands; heavens; levels of Gehinnom; and the number called up on Shabbat. Also included are a section (42a-44a) entitled the order of the world according to the order of the twenty-two letters comprised of alphabetic listings on years, the soul, Israel, holy vessels, and mo’adim, and the third section on vowels. Gershom Scholem suggests that Ginnat Egoz, based on Gikatilla’s description of the relationship between the nefesh and body (golem), and the body’s ability with the vital spirit that dwells in it to move back and forth, reflects the influence of German Hasidism. There are two diagrams, one dealing with the movement of gilgulim, the other with mystical combinations of letters.25

1615, Ginnat Egoz, Hanau

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

As noted above, Zinberg wrote that Gikatilla came to mysticism after being disappointed by philosophy. He expresses that feeling in Ginnat Egoz, quoting Gikatilla’s lament,

How dark and crooked are the paths on which my people wander. I saw persons who deny providence and wish to show that man’s fate depends entirely on the spheres and planets. Relying on the authority of Aristotle, they completely reject the idea of man’s freedom of will and power of choice. They refuse to take any account of whether man feels God in his heart. They insist that everything that occurs according to the iron laws that govern nature, and that God is not the ruler and guide of the world. They do not believe that the Torah is from heaven or that the universe was created at a definite moment. They believe in the eternity of the universe and that everything has been in motion throughout all time, according to precise laws in which no alteration can occur. On this basis they deny all miracles and wonders, for these would contradict such laws. They refuse to recognize that belief in miracles is the foundation of our Torah and reject it. Thus they deny the entire Torah.26

In an accompanying footnote Zinberg writes that Maimonides, in his Moreh HaNevukhim (Guide for the Perplexed), also recognized the contradiction between belief in miracles and Aristotle’s principle of the eternity of the universe, for the belief in the eternity of the universe contradicts the Jewish” religion and denies all miracles.

Ginnat Egoz is an important and influential kabbalistic work. It has been republished several times (Zolkiew, 1777, and Mohilev, 1798), and abridged as Ma’ayan Gannim by R. Eliakim ben Abraham of London (Berlin, [1803]).

In addition to the above titles, several others by Gikatilla remain in manuscript. Among them are a collection of responsa on such halakhic subjects as prayer, Shabbat, and Rosh Hodesh. Gikatilla authored a commentary on Shir ha-Shirim (Song of Songs); on the Shemitot, a theory of cosmic development based on the sabbatical year, as expounded in the Sefer ha-Temunah; and Sod ha-Nahash, kabbalistic revelations of the divine serpent. Those codices, and several others, albeit valuable, are beyond the scope of this article.

R. Joseph ben Abraham Gikatilla was, is, a person of significance. A kabbalist and prolific author, his works are influential and highly regarded, several frequently reprinted, and one, Sha’arei Orah, is considered a fundamental work of Kabbalah. To repeat, his contribution to Hebrew literature and the study of Kabbalah is significant. Nevertheless, as with other scholars and leading rabbinic figures, he too is not well-remembered today, although more so in kabbalistic circles, than others of his contemporaries.

1 Marvin J. Heller is an award winning author of books and articles on early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among his books are the Printing the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and several collections of articles.

2 Additional articles by Marvin J. Heller describing eminent rabbis and sages not well-remembered today in Sephardic Horizons are “Moses ben Baruch Almosnino: A Sixteenth Century Multi-Faceted Sephardic Sage in Salonika.” (Sephardic Horizons, 11: 4, Fall, 2021), reprinted in Further Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 151-165; “Jacob Judah (Aryeh) de Leão Templo: A Converso Scholar, a Jewish Hahkam” (Sephardic Horizons, 12:1, Spring 2022) reprinted in Further Essays in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book, (Leiden/Boston, 2024), pp. 184-201; “Solomon de Oliveyra: A Seventeenth Century Sephardic Sage” (Sephardic Horizons, Sephardic Horizons, 13, Issues 1-2 Winter-Spring 2023, reprinted in Further Essays, pp. 219-246; and “Jacob (Israel) ben Samuel Hagiz: Scion of a Family of Prominent Sephardic Sages” Sephardic Horizons, 14, Issue 2 - Spring 2024.

3 Kaufmann Kohler, M. Seligsohn, “Gikatilla, Joseph b. Abraham,” Jewish Encyclopedia V (New York, 1901-06), pp. 665-66.

4 Hersh Goldwurm, ed. The Rishonim: Biographical Sketches of the Prominent Early Sages and Leaders from the Tenth-Fifteenth Centuries (New York, 1982), p. 94-95; Idel, op. cit.; Gershom Scholem, Kabbalah (Jerusalem, 1974), pp. 53-54; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. place, and year printed, name of printer, number of pages and format, with annotations and bibliographical references II (Jerusalem, 1993-95), p. 410 [Hebrew].

5 Goldwurm, op. cit.

6 Moshe Idel, “Abulafia, Abraham ben Samuel,” vol. 1, Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem, 2007), pp. 3377-39.

7 Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York, 1954), pp. 194-96, 212; Mordechai Margalioth, ed., Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel III (Tel Aviv, 1986), cols., III col. 758-59 [Hebrew]; and Israel Zinberg, A History of Jewish Literature, translated and edited by Bernard Martin III(Cleveland, 1973), pp. 35-36.

8 Shimon Vanunu, Encyclopedia Arzei ha-Levanon. Encyclopedia le-Toldot Geonei ve-Ḥakhmei Yahadut Sefarad ve-ha-Mizraḥ II (Jerusalem, 2006), pp. 953-55 [Hebrew]. The references to Gikatilla by Caro also refer to two other responsa described as apocryphal, one dealing with kaddish, the other with an interruption in the Amidah prayer. Concerning this see R. J. Zwi Werblowsky, Joseph Karo, Lawyer and Mystic, (Philadelphia , 1977), pp. 180-81.

9 R. Moses de León (Moshe ben Shem Tov, c. 1240–1305) was a noted and influential kabbalist. Concerning de León see Gershom Scholem, “Moses ben Shem Tov de León,” vol. 14, Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem, 2007), pp. 554-55).

10 Margalioth, op. cit.

11 The Sefirot are defined as the “theory of ten creative forces that intervene between the infinite, unknowable God ("Ein Sof") and our created world.” The ten Sefirot are Keter, the Divine Crown; Hokhmah, Wisdom; Binah, Understanding; Hesed, Mercy; Din, Justice; Tif'eret, Beauty; Nezah, Eternity; Hod, Glory; Yesod, Foundation; Shekhinah, God's Presence in the World. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-ten-sefirot-of-the-kabbalah.

12 “Portae Lucis by Joseph Gikatilla, Augsburg, 1516,” Ursula and Kurt Schubert Archives The Center for Jewish Art.

13 Kaufmann Kohler, Peter Wiernik, “Riccio, Paulo (Latin, Paulus Ricius),” vol. 10, Jewish Encyclopedia, (New York, 1901-06), pp. 404-05.

14 John Edwards, The Jews in Chrisitian Europe, 1400-1700 (London, 1988), pp. 47-48; David B. Ruderman, Early Modern Jewry: A New Cultural History, (Princeton, 2010), p. 104

15 On the Riva di Trento press see David Amram, The Makers of Hebrew Books in Italy (Philadelphia, 1909, reprint London, 1963), pp. 296-302; Bloch, “Hebrew Printing in Riva Di Trento,” Published by The New York Public Library, 1933, pp. 89-110. Cardinal Madruzzo was succeeded as Cardinal in Riva by his nephew, Ludowic Madruzzo, in 1561. Less tolerant than his uncle, the press ceased to print Hebrew books the following year. Those books already in press were completed elsewhere.

16 Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printers’ Marks, (Jerusalem, 1943), pp. 29, 141 no. 46 [Hebrew].

17 Isaac Yudlov, Ginzei Yisrael, The Israe7 Mehlman Collection in the Jewish National and University Library (Jerusalem, 1984), p. 172 no. 1058 [Hebrew with English Appendix].

18 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_ben_Abraham_Gikatilla.

19 Asi Farber-Ginat, R. Joseph Gikatilla's Commentary to Ezekiel's Chariot: Sources and Studies in the Literature of Jewish Mysticism (Los Angeles, 1988), p. 16.

20 Scholem, Kabbalah, op. cit., p. 122.

21 The contents of Arzei Levanon, specified on the title page, are: Midrash Konen (2a-6b), on the origin of the world, the heavens, paradise, and hell; Ha-Emunah ve-ha-Bittahon (7a-32b), a kabbalistic work generally attributed to R. Moses ben Nahman (Ramban, 1194–1270) and so described on the title page, but now believed to have been written by R. Jacob ben Sheshet Gerondi (13th century); Sefer ha-Nikud (33a-40a); Sod ha-Hashmal (40b-42a) on the vision of Ezekiel, also by Gikatilla; Pirkei Heikhalot of R. Ishma’el Kohen Gadol (42b-46a), on Merkavah mysticism; Ma’ayin ha-Hokhmah (46b-47a), attbuted to R. Jacob ben Sheshet Gerondi, and Klalei Midrash Rabbah (48a-50a), abridged form of the methodological treatise on the Midrash Rabbah y R. Abraham ben Solomon ibn Akra.

22 Concerning the usage of the Mars and Minerva frame, see Marvin J. Heller, “Mars and Minerva on the Hebrew Title Page,” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 98:3 (New York, N. Y., 2004), pp. 269-92, reprinted in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2008), pp. 1-17.

23 Meir Benayahu, “The Books Printed in Venice at the Zanetti Press,” Asufot XII pp. 9-17 [Hebrew].

24 Isaac Yudlov, The Haggadah Thesaurus. Bibliography of Passover Haggadot: From the Beginning of Printing until 1960 (Jerusalem, 1997), p. 6 no. 39 [Hebrew].

25 Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York, 1954) pp. 194-96, 212; Margalioth, III col. 758-59 [Hebrew].

26 Zinberg, op. cit.

Copyright by Sephardic Horizons, all rights reserved. ISSN Number 2158-1800