Jacob (Israel) ben Samuel Hagiz:

Scion of a Family of Prominent Sephardic Sages1

By Marvin J. Heller2

Ein Yisrael, title page, 1645

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Among the many eminent families which have graced the pages of Jewish history is the Hagiz family. As with many other prominent and prestigious individuals and families who were communal sages and leaders in their time, recollections of them have faded over the years, history is often unkind to their memory. This is neither uncommon nor even an entirely unreasonable phenomenon, contemporary concerns and leaders taking precedence. Nevertheless, the contributions and importance of earlier individuals should not be forgotten; we should be aware and appreciative of their contributions to Jewish culture and history.3 Jacob (Israel) ben Samuel Hagiz was such an individual, a leading member of a prominent distinguished family, but again, not as well remembered as seems appropriate.

I

The Hagiz family falls into this category of sages who were leaders and contributed to contemporary culture, prominent in their time, but whose memory today is primarily limited to academic circles. Originally from Spain, the family went to Fez, Morocco, after the expulsion of the Jews from their former land in 1492. Members of the family became heads of the Castilian community of Megorashim (the exiled). Jewish settlement in Fez dates back close to the founding of the city by Imam Idris II in 808. Sages associated with early Fez include the grammarian R. Dunash be Labran, R. Judah Hayudi, who analyzed the structure of Hebrew, and most notably, R. Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi.4 Among the illustrious Jews who found refuge in Fez from the persecutions at Spain is Maimonides' father with his family, from 1152 to 1165, and Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon, Rambam) who was a resident there for several years.5

Among the young Spanish exiles who became members of the Fez community were the Hagiz family. According to Israel Zafrani, writing in 1596 in reference to Samuel ben Jacob Hagiz, Fez was “the place in which he and his forbearers are renowned.”6 Among the Hagiz family members raised and educated there was Abraham Hagiz (d. before 1563). He is noted as having been among the Castilian rabbis who were signatories to a takkanah (halakhic enactment, decree) in 1545, one of several issued in Fez at this time.7 Samuel Hagiz (d. c. 1570), likely the younger brother of Abraham Hagiz, was rabbi of Fez and the father of Jacob (Israel) Hagiz. He was among the leading scholars of Eretz Israel in the seventeenth century. Samuel’s grandson, also a Samuel (Samuel II), refers in his Mevakkesh Ha-Shem (below) to his grandfather’s biblical commentaries, crediting him with directing an important yeshivah, which is confirmed by his disciple Samuel ben Saadiah ibn Danan. Several of the takkanot issued at this time frequently bear his signature.8

Several members of the Hagiz family were the authors of highly regarded and frequently reprinted works. Among them are Jacob, Samuel II, and Moses Hagiz. Moses Hagiz (1671-c. 1750), however, belongs to a somewhat later generation than the members of the family we are presently concerned with; his works are not, therefore, addressed in this article but, perchance, may be addressed in a later article. We will address the Hagiz imprints in the order in which they were published beginning with Samuel II’s books. Thus Jacob (1620–1674) and Samuel (II) (1590 - 1633) are addressed out of order, chronologically.

II

Samuel Hagiz II left Morocco for Tripoli in Libya where he remained for some time, subsequently relocating to Venice. In the last location, he published the two works he authored, Devar Shemu’el and Mevakkesh Ha-Shem, both on the weekly Torah reading. After publishing those titles Samuel went to Jerusalem, residing there for the rest of his life.9 Samuel also edited R. Solomon ben Zemach Duran’s Tif'eret Yisrael (Venice, c. 1596).10

Devar Shemu’el, 1596

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

Although closely related, Devar Shemu’el and Mevakkesh Ha-Shem are distinct works. Both were printed in quarto (20 cm.) format (40: 258, [8]; 54 ff. [foliation says 58 in error]) by the Zoan (Giovanni) di Gara11 press in Venice in (1596=356) שנ"ו. Hebrew printing stopped shortly after the burning of the Talmud in Venice on October 21, 1553. The Di Gara press, active from 1564 to 1611, was the last and most successful of the Hebrew presses founded after printing resumed in Venice. The Di Gara press printed more than two hundred and seventy books, primarily in Hebrew letters, and only infrequently in non-Jewish languages.12

Both works by Hagiz share a similar architectural, pillared frame and text noting the family, including Samuel’s eponymous grandfather, the place of printing and date; the sole textual difference is a brief statement after the title describing each work. The title-page of Devar Shemu’el concisely informs that it is a commentary on the homilies in Devarim Rabbah. The verso of the title-page has a brief introduction from the editor, Israel ben Daniel Zifroni, describing it as a precious work, and commands וצוה, that it be joined with Mevakkesh Ha-Shem also written by the author. The text follows, Devar Shemu’el, is concluded with an index.

Zifroni's command (instruction) that the books be joined, that is, bound together, is not unreasonable or unconventional. His suggestion that the books were printed separately reflects the fact that at that time books were more often than not sold unbound, to be bound by the purchaser. There is no necessity, therefore, if the books were printed separately, that they be bound together, as one in all or even most instances. Avraham Haberman confirms this understanding writing that the two books were printed separately.13

The title-page of Mevakkesh Ha-Shem, Samuel ben Jacob’s second related work, states that it is three sermons on each and every parsha (weekly Torah reading). On the verso of the title-page of Mevakkesh Ha-Shem are prefatory remarks from the editor, Israel Zifroni, praising the book and its author, and including the remark “‘Let us offer praise אפרין נמטייה’ (Bava Mezia 119a) who set his path which the Lord made successful, coming from [the holy community] of Fez to [the holy community] of Venice to publish his books to benefit the public.” In the second paragraph, Zifroni writes that he has, for the purpose of completeness, put at the end of the book a commentary on all the homilies in Devarim Rabbah and entitled it Devar Shemu’el. However, as noted above, it likely was printed as a separate work.

Next is Samuel’s introduction (2a-2b) in which he informs that the reason for three discourses on every weekly parsha is that there will be a Shulhan Arukh (arranged table) so that each man can expound the insights of earlier sages on Mondays, Thursdays, and Shabbat. Samuel entitled the work Mevakkesh Ha-Shem for two reasons: first, that the Holy One, Blessed be He, asks from Israel that they occupy themselves with the Torah, as it says, “but you shall meditate on it day and night” (Joshua 1:8) “for she is your life” (Proverbs 4:13). Also, He prevails when Israel studies and fulfills the Torah, as the sages state, “My children have prevailed over Me, My children have prevailed over Me” (Bava Mezia 59b). That is, they give Me a victory over the nations who accuse Israel of not studying Torah. Secondly, all who seek the Lord to publicly expound any portion of the parsha will find what they seek without difficulty in it. The introduction concludes with the following acronym, the initial letters of the verses spelling Shemu’el:

I rejoice at your word, like one who finds great booty (Psalms 119:162)

שם

O how I love your Torah! It is my meditation all the day (119:8)

את-חקיך אשמר

I will also speak of your testimonies before

kings, and will not be ashamed (119:46)

ואדברה

I will keep your statutes; O do not forsake me utterly (119:46)

אתולי

If your Torah had not been my delight, I should have perished in my affliction (119:92)

לולי

The text follows (3a-258a) and then an index. These are the only editions of Devar Shemu’el and Mevakkesh Ha-Shem recorded by Ch. B. Friedberg in the Bet Eked Sepharim.14

III

We now turn to Jacob ben Samuel Hagiz, father of Samuel Hagiz II, whose works we just addressed. Jacob (Israel) Hagiz was born on 26 Shevat ש"פ (Friday, January 31, 1620), based on his responsa, in Fez, according to Mordechai Margalioth and Shimon Vanunu. In contrast, Hersch Goldwurm writes that Jacob’s place of birth is unknown, and that Jerusalem, Fez, and Leghorn (Livorno) have been suggested as birthplaces. Nevertheless, most sources accept Fez as Jacob’s place of birth. His name is frequently given as Jacob (Israel), the latter name having been added after one of several serious illnesses that he experienced.15

Jacob, an only child, was educated by his father, Samuel, and his mother, Sarah. Elisheva Carlebach informs that Jacob was only thirteen when his father died. His mother took responsibility for his education, which included “at least a rudimentary introduction to secular lore. In an epilogue to one of his books, Petil Tekhelot, p. v, Jacob wrote, ‘Investigate the sciences with all of your strength, and above all, the knowledge of Torah.’’’16

In Verona, he taught briefly in the yeshiva of R. Samuel Aboab (Rasha, 1610 –1694). In 1652, Jacob left for Venice, stayed there briefly and then relocated to Livorno, also residing there briefly. He was next in Pisa on the way to Jerusalem where he remained from 1658. Jacob’s prominence as an author of highly regarded works was one only of his many achievements.

In addition to his highly valued books, Jacob Hagiz led a yeshivah in Jerusalem. He was also the head of a rabbinic court there.17 His relocation to Jerusalem came after being approached while in Livorno by the wealthy and influential Vega brothers who, impressed by Hagiz, requested that he head a yeshiva in Jerusalem after a severe plague had broken out in Jerusalem. They urged Hagiz to relocate to found the yeshiva. He did so in 1658, living the “life of a recluse,” according to Heinrice Graetz.18 The yeshiva Hagiz established, Beis Yaakov, was highly regarded and is credited with aiding in the resettlement of Jerusalem. Among Hagiz’s students were many individuals of distinction, leaders of the next generation, such as R. Joseph Almosnino (1642–1689), R. Moses ibn Habib (1654-96), and R. Hezekiah da Silva (1659-98).

Less commendable among Hagiz’s students is Nathan ben Benjamin Ashkenazi of Gaza (1643/4–1680). Graetz describes Nathan as:

“a youth with superficial knowledge” who “concealed poverty of thought beneath verbiage. . . . A rich Portuguese, Samuel Lisbona, who had moved from Damascus to Gaza, asked Jacob Chages [sic] to recommend a husband for his beautiful, but one eyed daughter, and he suggested his disciple Nathan Benjamin. Thus he became connected with a rich house and in consequence of his change of fortune, lost all stability if he had any.”19

In strong contrast, Gershom Scholem describes Nathan as “a respected rabbinical scholar with kabbalistic leanings . . . he seems to have been a brilliant student, quick to understand and of considerable intellectual power.”20 Concerning the above narrative, Scholem relates that when Lissabona (sic) requested that Hagiz recommend a groom for his daughter “Hagiz selected his best student and Nathan went to live with his wife’s family in Gaza.”21

The parenthetical discussion concerning Nathan of Gaza, who is remembered today as the prophet of the false messiah, Shabbetai Zevi, is addressed here because Hagiz was a leading opponent, indeed “a vehement opponent of Shabbetai Ẓevi from the beginning, being one of the first to regard him as a false messiah, and he was one of those who excommunicated him in 1665.”22 Elisheva Carlebach addresses Jacob Hagiz’s response to the pseudo-messiah that he “and his circle were staunchly opposed to Sabbatai’s claims. In mid-summer of 1665, they issued a ban of excommunication against Sabbatai . . .”23

After the death of his first wife, Jacob remarried, becoming the son-in-law of R. Moses Galante (1620–1689), the most prominent contemporary rabbi in Jerusalem. Moses Hagiz, a prolific author and prominent authority in his own right, was an offspring of this marriage. Among Galante’s works is Elef ha-Magen, comprised of one thousand responsa. In 1674, Jacob Hagiz left Jerusalem for Constantinople to publish his Lehem ha-Pannimm, a commentary on the Shulhan Aruch. He passed away there, only fifty-four years of age, and that work was never published. His son, Moses Hagiz, wrote in the introduction to Halakot Ḳeṭannot, that Lehem ha-Pannimm is one of several of Jacob Hagiz’s works that were lost.

The Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book, which records publications from 1469 through 1863, attributes nine works to Jacob Hagiz.24 The first of these titles, according to the Thesaurus, are Tehilat Hochmah (1647), Dinnei Berakhot ha-Shahar (1648), Etz ha-Hayyim, and Igeret Ha-Mehor (1650), all published in Verona. These books, however, were preceded by Ein Yisrael, an adaptation of Jacob ibn Habib’s (c. 1445-c. 1515) classic Ein Ya’akov; aggadot of the Babylonian Talmud and some of the Jerusalem Talmud, accompanied by Hagiz’s commentary. Ein Ya’akov was first printed in Salonika in 1515; it was published in Verona in 1645. This is the sixteenth printing of Ein Ya’akov, several editions under the title Ein Yisrael.

This edition of Ein Yisrael (title-page, article header image) was published

in octavo format (80: 64 pp.) at the press of Francesco de’

Rossi. That press, active from 1645 to 1652, published more than twenty

Hebrew titles. De’ Rossi was encouraged to establish the press by Hagiz,

together with R. Samuel ben Abraham Aboab (1610-94). Elisheva Carlebach

credits Hagiz as being “solely responsible for the establishment of a

printing press in Verona, having brought and transported the type

himself.” She describes the books published in Verona as having a

distinctive style, that is, “a small pocket size format, to make the

works widely available and less cumbersome to carry.”25 Ein Ya’akov was among the titles proscribed and burned together with the

Talmud after the Pope's bull of August 1553, and subsequently placed on

the Index librorum prohibitorum. The Council of Trent, which

permitted the publication of the Talmud in 1564, and several other

previously prohibited works as well, imposed onerous conditions, among

them. The expurgation of passages was believed inimical to Christianity,

as well as prohibiting the publication of several Hebrew books under

their original names. The Talmud, for example, could not be reprinted as

such, but could be reissued only if that name were omitted, it now being

called shas. Ein Ya’akov was reissued as Ein Yisrael,

the second volume of the work being entitled Bet Yisrael. This edition of Ein Yisrael is on tractate Berakhot. The

title-page is followed by Hagiz’s introduction, where he gives several

reasons for writing on Ein Yisrael, among them to elucidate this

work as well as to provide an easily portable and less expensive edition

than is currently available. Below the introduction is the tail-piece

(above). The text follows in two columns in rabbinic letters. Also

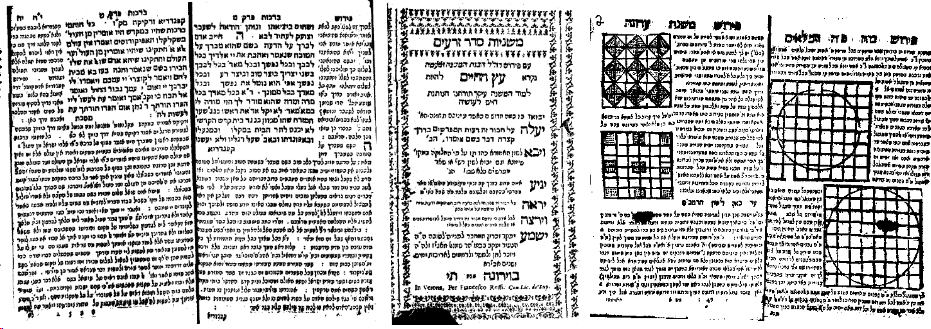

included are additions of R. Leone Modena (1571–1648).26 We now turn to Hagiz’s Tehilat Hochmah, on Talmudic methodology, printed

together with R. Samson ben Isaac of Chinon’s, Sefer Keritut.

Tehilat Hochmah, was published as a 16 cm. octavo (80: 4,

152, 64, 136, 16 pp.). There is one title-page only, with a frame

comprised of rows of florets, stating that it is: Sefer Keritut by R. Samson

of Chinon with Tehillat Hochmah, composed of many rules omitted

by the author [R. Samson] and I have gathered them, I the youth,

Jacob Hagiz, from the Talmud, Rashi, Tosafot, and from what is

brought in Halikhot Olam [by R. Yeshu’ah ben Joseph ha-Levi, 15th

century, see 16th Cent. 1: 272-73] and have culled from the best

(lit. clean fine flour), and from She’erit Yosef [Adrianople,

1554 by R. Solomon ibn Vega, d. c. 1559], and from the principles of R.

Joseph Caro, and from Yavin Shemu'ah [R. Nissim Solomon ben

Abraham Algazi, Venice, 1639]. I have brought them in a good order near

to the gates in a small volume with the principles of Kal va-Homer

(from the minor premise (kal) to the major) and other rules from

the leading earlier and later sages. . . .27 Tehilat Hochmah, as noted on the title-page, is a supplement to R.

Samson ben Isaac of Chinon’s Sefer Keritut. Samson ben Isaac was

among the last of the Ba’alei Tosafot. Born in Chinon, France, he is

considered among the leading sages of his generation. He authored

Sefer Keritut, on Talmudic methodology, a summation of

methodological principles and concerned with the hermeneutic

(interpretive) rules of Talmud study.28

He was the first Tosafist to write a work on

Talmudic methodology, written at the close of the period of the Ba’alei

Tosafot, it was first published in the sixteenth century

(Constantinople, 1515, Cremona, 1557). It has been reprinted seven

times, often with annotations or accompanying commentary, as in this

edition.

Both titles are set in a single column in rabbinic type. This edition of

Keritut follows the Cremona edition, except that the editor’s

introduction is omitted, notes are incomplete and where given are in an

abbreviated fashion, and the index accompanying that edition is not

printed here. Samson’s introduction is reprinted and there is an

introduction from Hagiz. Keritut concludes (161b) with a list of

the simanin prepared by Hagiz. Tehillat Hochmah follows

immediately. It does not have a separate title-page but does have its

own foliation. It begins with Hagiz’s introduction and, after the text

of Tehillat Hochmah, adds a kuntres, Orah Mishor,

for students on learning. Tehillat Hochmah concludes with an

index of the sixty-three kellalim that comprise the text of the

book. An example of an entry, albeit one of the smaller ones, is: Kellal 19. The tanna

repeats a matter to inform us, according to Rashi’s explanation, that

the tanna is occupied with this. It was not otherwise necessary

for him to make known to us that one who removes an object from one

domain to another domain is liable in only this manner. Ch. 1 (Shabbat 5b). Teḥillat Ḥokhmah has been republished several times, among them two

editions in Amsterdam, both in 1709 at the press of Solomon Proops, once

with Sefer Keritot and once alone, unaccompanied by Sefer

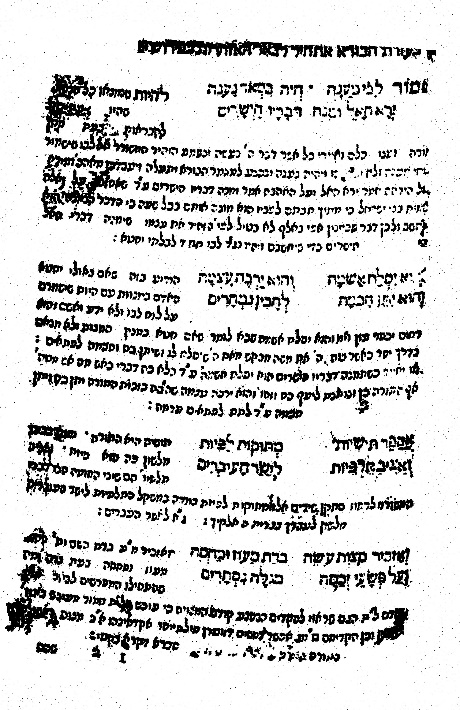

Keritot. Another work of interest, published the following year, is Dinnei Berakhot

ha-Shahar, a small octavo (80: 84 ff.) work on varies

aspects of prayer. The title-page describes Dinnei Berakhot ha-Shahar

as:

Dinnei Berakhot ha-Shahar

(the Laws on Morning Blessings) [Keriat Shema] Shabbat prayers, and tefilla (prayer), the

laws of Shabbat prayers, and the prayers of festivals and the laws

pertaining to beneficial blessings. The verso of the title-page many peshatim (literal explanations) and

desirable commentaries with introductions of the sages, halakhot,

novellae to delight students with hors d’oeuvres to wisdom that begins “How

beautiful and how pleasant is this prayer book, printed with fine

letters, attractive features not found previously,” and concluding “that

I will merit the public as your heart and eyes can see

אכי"ר [Amen, may it be so].”

The text is comprised of the order of prayers described on the title-page.

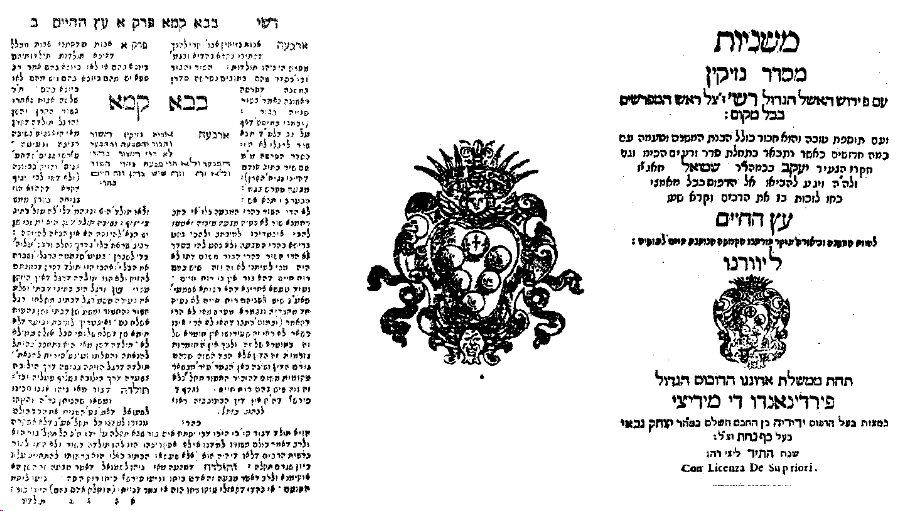

This is the only edition of Dinnei Berakhot ha-Shahar. In 1650, the de’ Rossi press published Mishnayot on Seder Zera’im,

the first Order in Mishnayot, with the commentary Etz ha-Hayyim

by Jacob Hagiz. Hagiz began work on Etz ha-Hayyim, his commentary

on Mishnayot, when he was twenty years old. He completed the entire work

before he was thirty. This first, partial edition is in octavo format 18

cm. (80:17, 135, 135-139,139-189, 4 ff.). The text is

comprised of the Mishnayot and Hagiz’s comprehensive commentary,

concluding with the Rambam on Mishnayot with diagrams (below). The title-page informs that the commentary brings the understanding

(interpretations) of commentaries in a concise fashion. It also includes

the language of Rashi and other commentaries without modification. The

text, however, is comprised of the Mishnah and Etz ha-Hayyim

only. At the bottom of the title-page in Latin is de’ Rossi’s name and

the statement Con. lic. De’ Sup., that is, permission to print.

A complete edition of Etz ha-Hayyim, on all of Mishnayot, was

published soon afterwards in Livorno (Leghorn) from 1653-56 at the press

of Jedidiah ben Isaac Gabbai entitled La Stampa del Kaf Nahat.29

The Gabbai press was so named after the commentary of his father, R.

Isaac ben Solomon, on Mishnayot, Kaf Nahat (Venice, 1609). In

contrast to the first printing of Etz ha-Hayyim, this edition was

published with the commentary of Rashi. It, too, is in octavo format (80:

24, 175; 284; 223; 302; 272; 368 ff.).

Livorno was part of the Medici domain, reflected on the title-pages. In this

Mishnayot, Grand Duke Ferdinand II (1610-1670), current ruler of the

Duchy is mentioned. The title-pages of Gabbai’s Livorno imprints have

the Medici escutcheon, the shield with five balls.30

On the bottom of the title-page is the phrase “Con

Licentia de Superiori et previlegio,” indicating that the book had

been approved for publication by the censors. The typographical material

and ornamentation used by La Stampa del Kaf Nahat was that of the famed

Bragadin press, acquired by Gabbai. Gabbai initially began where de’ Rossi left off, with Seder Mo’ed.

However, whether because demand was greater than Gabbai anticipated, or

to be able to provide his market with a complete set, Gabbai reprinted

Zera’im in 1654, before completing the remaining orders of

Mishnayot. The title-page text varies between them; Zera’im only, for example,

names the sponsor R. Abraham Israel Amnon, and contains the phrase from

the Rosh Hodesh and holiday liturgy, “may there rise, come,

reach, be seen, be favored, be heard,” each entreaty beginning a phrase

pertaining to Hagiz’s commentary. Five of the six volumes are dated in a

straightforward manner, for example Nashim, in the year

התיד

5414 from the Creation, that is, the full era (= 1654).

The sole exception is Seder Mo’ed, which is dated from the year,

“I came באתי to my garden” (Song of Songs 5:1), ([5]413 = 1653)

of the abbreviated era. Hagiz confirms in the introduction to Mo’ed that printing was begun in

Verona, but that, “the Lord aroused his spirit” to come to Livorno to

complete this work at the press of “the beloved of my soul, the

honorable Jedidiah ben Isaac Gabbai.” He continues, thanking Amnon, the

sponsor, “who took in his hand the deeds of Abraham, our father, to

benefit the public, may his praise stand forever.” For unspecified

reasons, Seder Tohorot, the last order in Mishnayot, preceded

Kodashim; mention of this being made by Hagiz in the afterword to

the latter. Also included are Maimonides’ commentary on Avot and

his introductions to Kodashim and Tohorot. Within the work, the

Mishnayot are encompassed by the commentaries of Rashi, and in his

absence that of R. Samson of Sens and Hagiz. Etz ha-Hayyim is a

large work, the six volumes totalling more than sixteen hundred pages,

printed in a small format, measuring only 15 cm. Two of Hagiz’s works were printed

in Venice: Petil Tekelet (1652) on the azharot by R.

Solomon Gabirol (c. 1021–c. 1057) and Hagiz’s responsa, Halakhot Ketanot

(1704). R. Solomon Gabirol, born in Malaga, residence

in Saragossa, died in Valencia, Spain, was a renowned poet and

philosopher. Among Gabirol’s works is Mivchar Ha-Peninim, a

sixty-four chapter ethical work. Azharot is a rhymed enumeration

of the six hundred and thirteen precepts of the Torah. Petil Tekelet, comprised

of Gabirol’s text with Hagiz’s commentary, was published at the

Commissaria Vendramina, the press of Giovanni Vendramin, founded in 1630

and active well into the eighteenth century. It was published in

duodecimo format (120: 70 ff.).

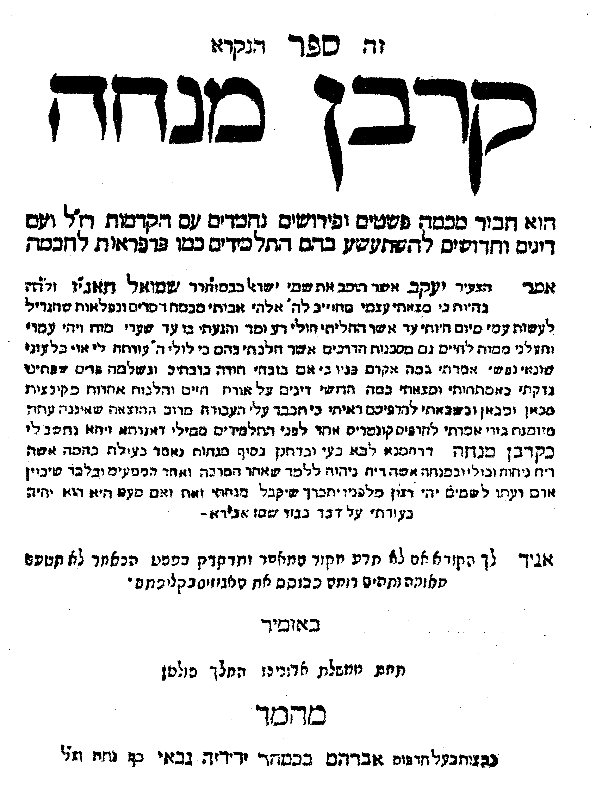

Several of Jacob Hagiz’s works were published

posthumously. Printed in the year following his passing (c. 1675), is

Korban Minhah, novellae, dinim, and homilies on

various subjects. Korban Minhah was published in Izmir (Smyrna),

Turkey, at the Kaf Nahat press of Abraham ben Jedidiah Gabbai (the son

of Jedidiah Gabbai) in quarto format (40: 56 ff.).31

That press was established in 1657 and Abraham Gabbai was active there

through 1660, and again from 1671 through 1675. Korban Minhah was

one of, if not, the last titles printed by Abraham Gabbai in Izmir.

The title-page, which has no decorative material, movingly explains the

reasons for bringing Korban Minhah to press, stating that it is

comprised of: many peshatim (literal

explanations) and desirable commentaries with introductions of the

sages, halakhot, novellae to delight students with hors d’oeuvres to

wisdom. Says the youth, Jacob,

who has the added name of Israel, ben Samuel Hagiz, I found myself

obligated to the Lord, God of my fathers, for the many kindnesses and

wonders and “the great things” (Joel 2:20) that He has done with me, for

I was previously ill, “an evil thing and bitter” (Jeremiah 2:19) “and I

came near to the gates of death” (cf. Psalms 107:18). But He was with me

and brought me up from death to life and from the perils of the way in

which I went. “Unless the Lord had been my help” (Psalms 94:17) those

who “hate my soul” (cf. II Samuel 5:8) would have devoured me. I said,

“With what shall I come before” (Micah 6:6) Him but with my thanksgiving

offering, as it is written, “so will we offer the words of our lips

[instead of calves]” (Hosea 14:3). I searched in my sack and found many

halakhic novellae on Orah Hayyim and halakhot from here and there

and when I brought them to press I saw that it was difficult due to the

great expense that was not available to me. I thought then to print one

kunteres before the students and it be considered for me as a

Korban Minhah . . . . The title-page is undated. The text is in a single column in rabbinic type,

excepting headers and initial words. Each of the paragraphs are

numbered, the last being 424. An example of an entry is: 6 Yalkut “into the garden

of nuts (egoz)” (Song of Songs 6:11). Even though the opening is

not open to a mitzvah it is open to a physician, that is, a poor

person can find a place thorough his illness to atone. Another meaning:

egoz, this is Abraham for egoz is found in, “forget your own people, and

your father’s house” (Psalms 45:11): vine, this is Isaac, there is Laban

and Edom. Jacob and Esau. “pomegranates are in bloom” (Song of Songs

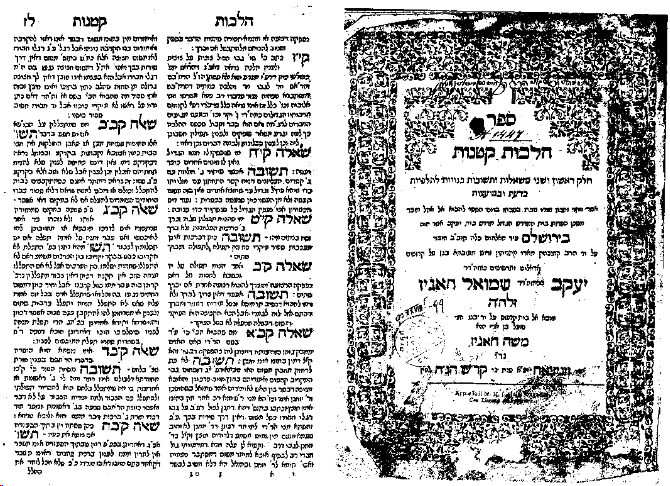

7:13) Jacob and his tribes fill all the peoples. Our last Jacob (Israel) Hagiz title is

Halakhot Ketanot, a volume of responsa. It was brought to print at

the Bragadin press in Venice by his son Moses Hagiz. It was published as

a 27 cm. ([4], 71, 9 ff,) work. The title-page has an attractive

border, somewhat worn in the reproduction. It is dated with the

chronogram, “When the priests enter,

they shall not proceed from the consecrated place to the outer court

without first leaving here the vestments in which they minister; for the

[vestments] are consecrated (כי קדש הנה

(464 = 1704 Before proceeding to the

area open to the people, they shall put on other garments” (Ezekiel 42:14).

The title-page informs that it is parts one and two of

the sheilot and teshuvot (responsa) “ordered as a model to

emulate” (cf. Song of Songs 4.4).

The text, as noted on the title-pages, is in two parts, the first part of

two hundred and eighty two responsa, part two of three hundred and

eighteen responsa, covering all four parts of the Shulhan Arukh.

At the end of the volume is a bakashah (entreaty), an index of

the entries, an addenda, errata, and a brief apologia from the editor,

R. Meshullam Zalman ben Abraham Baruch. The responsa are generally practical, brief and varied. An unusual aspect of

a cluster of several responsa is described by Matt Goldish. Several

examples, beginning with (#240) inquire whether: a blessing on the marvelous is to

be recited upon seeing an Ethiopian, that is, a black person. In his

reply, Hakham Hagiz discusses the occurrences of white people born of

black parents and black people born of white parents. In query #245 he

speaks of his own response in Italy and seeing Siamese twins, one of

whom is alive but inert and remains attached to his healthy brother.

Query #249, again from Italy, concerns the case of Siamese twin chicks.

He says they were made during the six days of creation, meaning they are

a unique creature fashioned by God from the beginning of time. . . .One

gains the impression that the legal questions asked in these cases are a

mere pretext for discussing strange creatures, they hardly seem pressing

problems of Jewish law.32 These unusual responsa notwithstanding, Halakhot

Ketanot addresses more practical various halakhic issues, reflecting

Hagiz’s great erudition. Most of the responsa are quite concise, as can

be seen form the following examples (f. 4): Sheilah 17: One who says I

accept upon myself a fast for atonement for my iniquities. How many,

for how long does he have to fast? Also included are responsa from Moses Hagiz. This is the only edition of

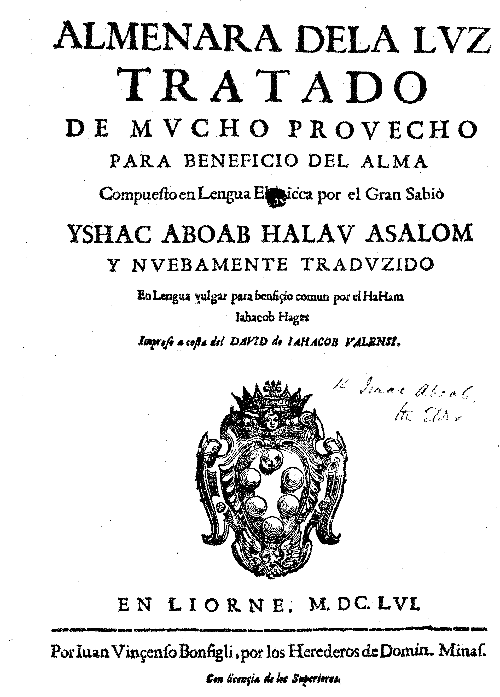

Korban Minhah. In addition to his Hebrew works, Hagiz

abridged and translated R. Isaac Aboab’s fourteenth popular ethical

religious work Menorat ha-Ma’or into Spanish. The

Spanish title is Almenara dela luz: tratado de mucho provecho para beneficio del alma,

Beacon of light: very useful treatise for the benefit of the soul. It was printed

in 1656 in Livorno, by Juan Vincenso Bonfigli as a 12 cm. work ([6], 270

pp.), sponsored by David de Iahacob Valensi. Almenara dela luz: tratado was translated “por

benefisio commun.” Hagiz’s “targeted readers were those who

‘no son muy corientes en declaros de nuestros Sabios, y en lengu ae ulgar

porge la poco corientes en el Ebraico.”

Hagiz wrote that these conversos “were living blindly until they learned

the basics of religious thought and practice.” In contrast to his other

books, which were “generally pocket-size, the

Almenara de la Lluz was produced in a large handsome, beautifully bound format intended as a

reference work and adornment for the libraries of prosperous

ex-Marranos.”33

Note the Medici emblem on the title-page.

The Hagiz family was a distinguished, productive, and prestigious family.

Several members held important rabbinic positions, as communal rabbis or

heads of yeshivas. In addition, they were the authors of highly regarded

books of value. Nevertheless, as in so many cases, as noted above, time

has not been kind to memories of them; they are generally not well

remembered outside of rabbinic and/or academic circles. In this article

we have noted the lives and works of several Hagiz family members,

Abraham, Samuel, Jacob (Israel) ben Samuel, and Samuel ben Jacob (II). Jacob (Israel) Hagiz was the most prolific of these family members. His

works are primarily addressed herein. An erudite individual, Jacob’s

books are varied, encompassing aggadah, Mishnah, Talmudic methodology,

aspects of prayer, as well as a commentary on azharot, homilies,

and responsa. In addition, Hagiz translated R. Isaac Aboab’s Menorat

ha-Ma’or into Spanish for the benefit of conversos. As the head of a

prominent yeshivah, Jacob Hagiz was responsible for and can be credited

with several of the next generation’s prominent rabbis. One unfortunate

exception was the prophet of the pseudo-messiah Shabbetai Zevi. In that

case, however, Hagiz was a leader, indeed an early and vehement opponent

of that movement. In closing, Jacob (Israel) Hagiz was a prominent

and outstanding member of a distinguished family. Both he, his family,

and their many achievements, should be warmly recalled. 1

I would, once again, like to thank Eli Genauer for his observations and comments. 2

Marvin J. Heller is an award winning author of books and articles on

early Hebrew printing and bibliography. Among his books are the Printing

the Talmud series, The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Hebrew

Book(s): An Abridged Thesaurus, and several collections of

articles. 3 Several other prominent

Sephardic sages and families were also the subject of articles in

Sephardic Horizons. They are Marvin J. Heller, “Moses ben

Baruch Almosnino: A Sixteenth Century Multi-Faceted Sephardic Sage

in Salonika.” (Sephardic Horizons, 11: 4, Fall, 2021); “Jacob

Judah (Aryeh) de Leão Templo: A Converso Scholar, a Jewish Hahkam”

(Sephardic Horizons, 12:1, Spring 2022); “Solomon de Oliveyra:

A Seventeenth Century Sephardic Sage” (Sephardic Horizons, 13: 1-2. Winter-Spring 2023),

and “The Albelda Family: Moses and Moses Jacob Albelda: Prominent, Eminent, Scholars” (Sephardic

Horizons, 13: 3, Summer 2023). 4 André N. Chouraqui, Between East and West, a

History of the Jews of North Africa (Philadelphia, 1968), pp. 82-84. 5 It appears that

Jewish relationships were generally, albeit not always, good with

their Muslim neighbors. Not to be excessively repetitive, and noted

previously, in Marvin J. Heller, “A Fleeting Moment, A Short-lived Press: Hebrew Printing in Sixteenth

Century Fez” (Sephardic Horizons, 11:1, Winter, 2021),

is an incident related by André N. Chouraqui, Between East and

West, a History of the Jews of North Africa (Philadelphia,

1968), p. 38-39, which illustrates a positive side of Jewish

relations in Morocco. It is a story concerning Yahya ben Yahya ben

Mohammed, the last emir of the branch of the Idrises. Yahya wanted a

young Jewess of Fez, attempting to seize her while in her bath. The

townspeople revolted, forcing Yahya to seek refuge in the Andalusian

quarter where he succumbed in the night. Chouraqui concludes that

this “shows that the townspeople of Fez were concerned for the

welfare of the Jews and their women and may be accounted for by the

strong Berber influence that remained in the town.” Relations were

not always positive, for in 1275 a mob attacked the mellah (the

Jewish quarter), killing forty Jews where Muslims were forbidden to

enter. 6 Elisheva Carlebach, The Pursuit of Heresy: Rabbi Moses

Hagiz and the Sabbatian Controversies (New York, 1990), p. 20. 7

Haim Zafrani, “Hagiz,” Encyclopedia Judaica (EJ), vol. VIII

(Jerusalem, 2007), p. 226. 8 Yosef ben Naʼim,

Malkhe Rabanan:

Toldot Rabane Maroḳo mi-Yemot ha-Geʼonim ʻad Shenat 691 (Jerusalem, 1998),

p. 123 [Hebrew]; Zafrani, “Hagiz,” EJ, vol. VIII, pp. 226-27. 9 Shimon Vanunu, Encyclopedia

Arzei ha-Levanon. Encyclopedia le-Toldot Geonei ve-Ḥakhmei Yahadut

Sefarad ve-ha-Mizraḥ IV (Jerusalem, 2006), pp. 2174 [Hebrew] 10

Meyer Kayserling,

M. Seligsohn,

H. Brody,

Richard Gottheil,

“DURAN, DURAND, or DURANTE,” Jewish Encyclopedia V (New York, 1901-06), p. 18). 11 Frequently referred to as

Giovanni di Gara, the name Giovanni is derived from Zoan, or Iohannes. 12 Concerning the di Gara press

see A. M. Habermann, Giovanni Di Gara: Printer, Venice 1564-1610. ed. Y. Yudlov

(Jerusalem, 1982), pp. ix-xvi [Hebrew]. 13 Habermann,

Giovanni Di Gara, p. 81 no. 160. 14 Ch. B. Friedberg,

Bet Eked Sepharim, (Israel, n. d), daled 126, mem 385 [Hebrew]. 15 The following discussion

of Jacob Hagiz’s biography is a composite of overlapping data from

Gotthard

Deutsch,

Lazarus Grünhut, “Hagiz Jacob” Jewish Encyclopedia

VI (New York, 901-06), p. 151; Hersch Goldwurm, The Early Acharonim (Brooklyn, 1989), pp.

183-84; Mordechai, Margalioth, ed.,

Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel III (Tel Aviv, 1986), cols.

859-62 [Hebrew]; David Tamar, ”Hagiz, Jacob (Israel;

1620–1674),” Encyclopedia Judaica, V 8, pp. 226-27; and Vanunu, op. cit. II, pp. 1140-41. 16 Carlebach, pp. 20-21. 17 Matt Goldish,

Jewish Questions: Responsa on Sephardic Life in the Early Modern

Period (Princeton and Oxford, 2008), p. lx. 18 Heinrich Graetz,

History of the Jews V (Philadelphia, 1898, reprint 1956), p.126. 19 Graetz, V, p. 130. 20 Gershom Scholem,

“Nathan of Gaza,” Encyclopedia Judaica XV, pp. 15-17. 21 Gershom Scholem,

Sabbatai Sevi. The Mystical Messiah 1626-1676 (Princeton, 1973), pp. 201,202. 22 Tamar, op. cit. 23 Carlebach, p. 31. 24

Vinograd, Yeshayahu. Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. place, and

year printed, name of printer, number of pages and format, with

annotations and bibliographical references I (Jerusalem, 1993-95), p. 229 [Hebrew]. 25 Carlebach,

The Pursuit of Heresy, p. 21. Numerous Talmudic tractates, albeit

printed somewhat later, were also in small format. Marvin J. Heller,

Printing the Talmud: A History of the Individual Treatises

Printed from 1700 to 1750 (Leiden, 1999), p. 3, maintains that

“about fifty percent of the individual treatises issued during the

first half of the eighteenth century were small-format editions,

generally between 16 and 20 cm, rather than the larger folio-size

volumes associated with complete Talmud editions. In the

small-format volumes, a standard page (amud) was often

printed over two pages (double pages), enabling the printer to use a

larger font than would have been possible by adhering to the

standard composition.” The title-pages of these tractates frequently

state that they were “prepared in a small volume so that a person

can carry it in his coat pocket, and look into it also when he is on

the way.” 26 This is the

sixteenth printing of Ein Ya’akov, several editions under the

title Ein Yisrael (Vinograd, I, p. 114.). Concerning the

Verona press of de’ Rossi see Marvin J. Heller, “Hebrew Printing in

Verona: Resumed, but Briefly.” Gutenberg-Jahrbuch (Mainz,

2017), pp. 155-69, reprinted in Essays on the Making of the Early

Hebrew Book, (Leiden/Boston, 2021), pp. 338-59. 27 Marvin J Heller,

The Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus,

Vol. I (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 20110), pp. 632-33. 28 Margalioth, IV

(cols. 1372-73 [Hebrew]); Israel Moses Ta-Shma, EJ Vol. 17, p. 753. 29

Concerning the Gabbai press see Marvin J. Heller,

“Jedidiah ben Isaac Gabbai and the First Decade of Hebrew Printing

in Livorno.” Los Muestros, part I, no. 33 (Brussels, 1998), pp.

40-41; part II, no. 34 (1999), pp. 28-30, reprinted in Studies in

the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Leiden/Boston, 2008), pp.

165-77. 30 This pressmark was only

used by Gabbai in Livorno. Elsewhere he employed the three crowns ornament, first used by the

press of Aluise Bragdine. 31 Concerning Hebrew

printing in Izmir see Marvin J. Heller, “Kaf Nahat and Hebrew

printing in Izmir” Los Muestros, (Brussels, 2009) part 1, no.

75, pp. 7-8; part 2, no. 76 pp. 7-8; part 3, no, 77, pp. 7-8,

reprinted in Further Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew

Book (Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 103-15).and Avraham Yaari,

“Hebrew Printing at Izmir,” Areshet (Jerusalem, 1972), Vol.

1:97-100 and Korban Minhah, p. 125 no. 16 [Hebrew]. 32 Goldish,

Jewish Questions, p. 107. 33 Carlebach, p.23.

Ein Yisrael, title page and tail piece on the right, 1645

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Tehilat Hochmah- Sefer Keritut, 1647

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

Dinnei Berakhot ha-Shahar, 1647

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Mishnayot Seder Zera’im, Verona, 1650

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Mishnayot Seder Nezikin, Livorno, 1654 with the Medici escutcheon

(shield with five balls)

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

IV

Petil Tekelet, 1652

Courtesy of the Library of Agudas Chassidei Chabad Ohel Yosef Yitzhak

Korban Minhah, title-page, 1675

Courtesy of Hebrewbooks.org

Halakhot Ketanot, title-page on right, 1704

Courtesy of the National Library of Israel

Teshuvah: It is possible that he should fast all his days. However, it is understood until he

says this was not my intent.

Sheilah 22: When the hatan and callah (groom and bride) wrap themselves in a talis should they make

a blessing?

Teshuvah: Whenever there is a primary עיקר and secondary

טפלה the blessing is made by the

primary. Here the man is the primary since he wears the talis and

spreads its corners alluded to by “Spread your robe over your handmaid” (Ruth 3:9).

Almenara de la luz, title-page, 1656

Courtesy of

Google BooksV